Spec Ops: The Line: Difference between revisions

From GameLabWiki

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

''Spec Ops: The Line'' tries to separate itself from the classical third person military shooter genre. Most outstanding is the introduction of decision making within the game and using storytelling to show war brutality and the psychological damages caused by being involved in war. In order to create situations in which the player must question his own morality, the game uses dilemma situations with limited time for the player to think them over, which often are a matter of life and death, highlighting the brutality of war. | ''Spec Ops: The Line'' tries to separate itself from the classical third person military shooter genre. Most outstanding is the introduction of decision making within the game and using storytelling to show war brutality and the psychological damages caused by being involved in war. In order to create situations in which the player must question his own morality, the game uses dilemma situations with limited time for the player to think them over, which often are a matter of life and death, highlighting the brutality of war. | ||

<youtube>https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wD661k1UpvQ</youtube> | <youtube>https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wD661k1UpvQ</youtube><ref group="Further Information ">https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wD661k1UpvQ</ref> | ||

====The Story==== | ====The Story==== | ||

[[File:The Delta Force Team arrives in Dubai.png|thumb|The Delta Force Team arriving in Dubai after crashing with the helicopter in the opening scene.]] | [[File:The Delta Force Team arrives in Dubai.png|thumb|The Delta Force Team arriving in Dubai after crashing with the helicopter in the opening scene.]] | ||

Six months before the playable story, Dubai got caught by a series of heavy sandstorms. The situation was kept secret by politicians and the media, while the upper class left the city, leaving behind many people in Dubai. A Battalion, called the „damned 33rd“ from the US Army was on its way back from a Mission in Afghanistan when the sandstorms started and their commander, Colonel Konrad decided to help evacuate the city of Dubai. The Battalion, under his command, took full control over the trapped civilians but could not manage the situation properly. After riots, caused by the lack of resources, like food and water, Konrad started to sacrifice some civilians to save others. This made some members of the 33rd turn against Konrad and his cruel leadership. Many tried to stop him from being in charge and but of them were caught and executed as traitors. A secret squad was sent to Dubai by the CIA and organised the local civilians to stand up against the 33rd. After heavy fights in Dubai between Konrads 33rd and the local people, lead by the CIA, Konrad announced their retreat, and they lead a caravan out of Dubai. But as time passed and the caravan was never seen, the US Army received a brief radio message from Konrad, saying the evacuation failed. The US Army decided to send in a Delta Force Team lead by Captain Martin Walker together with First Lieutenant Alphonso Adams and Staff Sergeant John Lugo. Their mission was to investigate about the situation, to find survivors and a way to evacuate the civilians out of Dubai. The playable story begins with the Delta Force Team arriving in Dubai. | Six months before the playable story, Dubai got caught by a series of heavy sandstorms. The situation was kept secret by politicians and the media, while the upper class left the city, leaving behind many people in Dubai. A Battalion, called the „damned 33rd“ from the US Army was on its way back from a Mission in Afghanistan when the sandstorms started and their commander, Colonel Konrad decided to help evacuate the city of Dubai. The Battalion, under his command, took full control over the trapped civilians but could not manage the situation properly. After riots, caused by the lack of resources, like food and water, Konrad started to sacrifice some civilians to save others. This made some members of the 33rd turn against Konrad and his cruel leadership. Many tried to stop him from being in charge and but of them were caught and executed as traitors. A secret squad was sent to Dubai by the CIA and organised the local civilians to stand up against the 33rd. After heavy fights in Dubai between Konrads 33rd and the local people, lead by the CIA, Konrad announced their retreat, and they lead a caravan out of Dubai. But as time passed and the caravan was never seen, the US Army received a brief radio message from Konrad, saying the evacuation failed. The US Army decided to send in a Delta Force Team lead by Captain Martin Walker together with First Lieutenant Alphonso Adams and Staff Sergeant John Lugo. Their mission was to investigate about the situation, to find survivors and a way to evacuate the civilians out of Dubai. The playable story begins with the Delta Force Team arriving in Dubai. | ||

[[File:Screen capture 2 gif.gif|thumb|The main character 'Walker' having hallucinations ]] | <br />[[File:Screen capture 2 gif.gif|thumb|The main character 'Walker' having hallucinations ]] | ||

====Plot (Spoiler)==== | ====Plot (Spoiler)==== | ||

After about the first half of the game, things begin to take a turn. Walker starts to slowly loose his sanity, and his visual hallucinations start to appear more and more frequently: Soldiers appearing out of nowhere, landscapes changing when walking past them, flashbacks to past events and dreams of being trapped in an unescapable, hell-like maze. At one point Walker relives the opening scene, realising he’s been going through this before. In the last chapter, when he is finally confronted with Konrad, he discovers that Konrad has been dead for a long time, while he’s talking to him in his imagination, seeing him as a ghost. He also realises he’s been talking to himself throughout the whole game, which explains some of the nonsensical answers he received from Lugo and Adams. Many events turn out to be only products of his imagination and never actually happened in real life. | After about the first half of the game, things begin to take a turn. Walker starts to slowly loose his sanity, and his visual hallucinations start to appear more and more frequently: Soldiers appearing out of nowhere, landscapes changing when walking past them, flashbacks to past events and dreams of being trapped in an unescapable, hell-like maze. At one point Walker relives the opening scene, realising he’s been going through this before. In the last chapter, when he is finally confronted with Konrad, he discovers that Konrad has been dead for a long time, while he’s talking to him in his imagination, seeing him as a ghost. He also realises he’s been talking to himself throughout the whole game, which explains some of the nonsensical answers he received from Lugo and Adams. Many events turn out to be only products of his imagination and never actually happened in real life. | ||

| Line 22: | Line 20: | ||

In the end of the game, the player is given multiple choices. Either they can shoot the imagination of Konrad to mark the end of dealing with moments of insanity. Or the player can choose to commit suicide. | In the end of the game, the player is given multiple choices. Either they can shoot the imagination of Konrad to mark the end of dealing with moments of insanity. Or the player can choose to commit suicide. | ||

<youtube>https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MFI-yWFURCk</youtube> | <youtube>https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MFI-yWFURCk</youtube><ref group="Further Information ">https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MFI-yWFURCk</ref> | ||

==Research-Relevant Topics of the Game== | ==Research-Relevant Topics of the Game== | ||

| Line 28: | Line 26: | ||

====Controls==== | ====Controls==== | ||

In ''Spec Ops: The Line'', the Player takes control of the main character: „Captain Martin Walker“. The basic controls are mostly similar to a classical third person shooter, with the camera looking above the shoulder of the character and other elements such as taking cover behind obstacles, picking up enemy’s weapons and managing resources like ammunition and grenades. You can also make orders to the other members of the Team, Adams and Lugo. You can tell them to concentrate their fire on specific enemies, use flash grenades to blind groups of enemies or push towards a specific direction. In its core, it is played like any other military shooter game. Furthermore, apart from some collectable items that tell a short story about past events, there is not much to explore in the mostly linear levels. The game is split in into total of 15 Chapters, with an average playtime of six to seven hours. | [[File:Bildschirmfoto Mörser.png|thumb|The Delta Force Team using the white phosphor bomb]] | ||

In ''Spec Ops: The Line'', the Player takes control of the main character: „Captain Martin Walker“. The basic controls are mostly similar to a classical third person shooter, with the camera looking above the shoulder of the character and other elements such as taking cover behind obstacles, picking up enemy’s weapons and managing resources like ammunition and grenades. You can also make orders to the other members of the Team, Adams and Lugo. You can tell them to concentrate their fire on specific enemies, use flash grenades to blind groups of enemies or push towards a specific direction. In its core, it is played like any other military shooter game. Furthermore, apart from some collectable items that tell a short story about past events, there is not much to explore in the mostly linear levels. The game is split in into total of 15 Chapters, with an average playtime of six to seven hours.<ref><nowiki>https://howlongtobeat.com/game?id=8898</nowiki> </ref><br /> | |||

====Decision making==== | ====Decision making==== | ||

The way in which ''Spec Ops: The Line'' differs mostly from other games within the third person shooter genre is how the player must decide his own destiny within the story, as oppose to it being pre-determined. All of the multiple decisions that have to be made within a play-through stay inside the basic game mechanics. Decisions are not made by simply selecting one or the other option, by clicking at a certain point or pushing a certain button, but by choosing to perform between two specific actions or not acting at all. In praxis, you are confronted with situations where you have to act in a specific way to make a choice, like shooting a soldier or waiting to let him get away. Or perhaps opening fire or staying quiet so to not loose stealth. These specific decisions can affect the fate of the team as well as the life of the civilians. They also have an impact on the relationship between Walker and his teammates, causing them to react differently. Walker suffers psychologically after a negative outcome and he begins to go insane, which gradually worsens as the game progresses He starts to see visual hallucinations and his behaviour becomes more violent and out of control. | The way in which ''Spec Ops: The Line'' differs mostly from other games within the third person shooter genre is how the player must decide his own destiny within the story, as oppose to it being pre-determined. All of the multiple decisions that have to be made within a play-through stay inside the basic game mechanics. Decisions are not made by simply selecting one or the other option, by clicking at a certain point or pushing a certain button, but by choosing to perform between two specific actions or not acting at all. In praxis, you are confronted with situations where you have to act in a specific way to make a choice, like shooting a soldier or waiting to let him get away. Or perhaps opening fire or staying quiet so to not loose stealth. These specific decisions can affect the fate of the team as well as the life of the civilians. They also have an impact on the relationship between Walker and his teammates, causing them to react differently. Walker suffers psychologically after a negative outcome and he begins to go insane, which gradually worsens as the game progresses He starts to see visual hallucinations and his behaviour becomes more violent and out of control. | ||

==== | ====Different types of decisions==== | ||

Within the game, there are basically only two types of decisions. First there are those that have small or even none direct impact on the story or the outcome of a situation. This type applies for most of the decisions made throughout the game. Their impact is often not clearly shown to the player. Decisions, like this, don’t have any long term consequences or at least not any that are noticeable. | |||

For example: | |||

[[File:Gould Hinrichtung.jpg|thumb|The CIA Member 'Gould' is about to be executed]] | |||

Relatively early in the game, we see a member of the CIA, called Gould, who wanted to stand up against the leadership of Konrad. He wasn’t successful and got caught instead. He is about to get punished for what his betrayal and is surrounded by soldiers that will execute him in front of a building. To that scene, Walker and his team walks up. They stay hidden, observe the situation and discuss about what to do. Walker, Adams and Lugo discuss if they should open the fire on the soldiers in order to safe Goulds life, while losing their camouflage or if they should let him die but stay hidden. It seams like a real decision where both actions have arguments for and against doing. The team discusses and the player decides by either opening the fire or by waiting until the soldiers executed Gould. There is no indicator that shows the player how much time is given to make a decision. | |||

When decided to save Gould, the soldiers start firing back immediately and call for support. After the battle against a huge wave of enemies, there is a cutscene, in which the Delta Force Team runs to Gould, finding out he died from loosing too much blood due to his earlier injuries. | |||

When decided to stay hidden and not starting fire; The CIA soldiers execute Gould and after that they notice the Delta Force Team in their hideout by accident. They start shooting and a slightly smaller wave of enemies has to be defeated. | |||

Both decisions lead to an almost similar outcome, none of them was the right or the wrong decision. This Example shows how decisions work in ''Spec Ops: The Line''. Only the way the team members talk to each other is influenced by decisions like this one. There are no further consequences neither in short nor in long sight. | |||

==Related Research Approaches== | ==Related Research Approaches== | ||

====Agency according to Salen==== | ====Agency & Meaning according to Salen==== | ||

The whole process of Walker slowly loosing his mind and suffering from psychotic trauma reflects on the player and makes them feel responsible. | |||

Meaningful Play, as described by Salen, develops in terms of the descriptive meaningful play, through the different, possible outcomes of the decision.<ref>Salen, Katie. Zimmerman, Eric. Rules of Play: game design fundamentals. Unit 1. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2004, p. 34.</ref> The player is informed about the short-term possible outcomes, mostly tangible through cutscenes and the conversations between Walker and the other members of the team. | |||

Meaning is, as Salen suggests, is generated by putting the player into bleak situations where they are forced to make a decision in order to prevent the main character from the worst possible outcome, while still trying to survive and complete the mission. Meaningful play is not achieved through long term consequences. It is more about forcing the player to act fast and act within your own moral standards. It is not possible to differentiate the decisions in right or wrong. Most decisions become dilemmas and have negative outcomes only, so the player has to try to pick the one that makes the other characters suffer less. | |||

The process of decision making fits in the semiotic system invented by Salem and Zimmerman, which is their approach to show that the meaning created has to fit within the system it is part of, because one goal of the game is to trigger repentance and to make the player question the whole intention of being entertained by war games and war in general. | |||

====Baumgartner==== | ====Baumgartner==== | ||

Since ''Spec Ops: The Line'' was published in 2012 it fits right in the era where the decision turn happened in video games, according to Robert Baumgartner.<ref>Baumgartner, Robert. Prozeduale Entscheidungslogik im Computerspiel, In: Ascher, Franziska. „I’ll remember this“. Funktion, Inszenierung und Wandel von Entscheidungen im Computerspiel, Glückstadt, 2016, p. 258.</ref> But it differences itself from the decisions described by him in the case, that decisions made, are concrete moments of decision making instead of not noticeable decisions made by just playing the game. The lack of letting the player know, whenever he made a decision, that will have consequences later in the game goes against his understanding of agency. Makro-decisions are not present either so it’s not possible to categorise ''Spec Ops: The Line'' in one of both categories. It neither fits in a game that uses structural decisions nor in a game that uses substructural decisions to generate agency. | |||

Meaning and agency is suggested but does not apply, except for the last decision in the game. This leaves us with a fake, not existing feeling of agency, while most decisions will not have any impact on the narrative. | |||

====Fullerton and the decision scale==== | ====Fullerton and the decision scale==== | ||

Fullerton and the decision scale: | |||

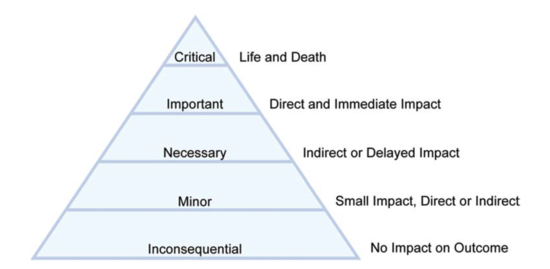

Tracy Fullertons decision scale can be used to define different types of decisions by categorising them based on critical level. | |||

Decisions are split up in five different categories: | |||

[[File:Bildschirmfoto Fullerton.png|thumb|550x550px|Decision scale - Fullerton]] | |||

*Inconsequential - „No Impact on Outcome“ | |||

*Minor - „Small Impact, Direct or Indirect“ | |||

*Necessary - „Indirect or Delayed Impact“ | |||

*Important - Direct and Immediate Impact“ | |||

*Critical - „Life and Death“ | |||

Decisions in ''Spec Ops: The Line'' may often be categorised as Important or even Critical. The Game tries to suggest a feeling of making important decisions to the player by putting them in situations where they has to decide about other peoples life and death.<ref>Fullerton, Tracy. Game Design Workshop, A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. Boca Raton, 2019, p. 356.</ref> | |||

But Fullerton takes further differentiations. Some of those sub-categories are present in ''Spec Ops: The Line'' and need to be considered. | |||

Hollow decisions are decisions that turn out to have no real consequences at all. | |||

Obvious decisions that are not a real decision. | |||

Uniformed decisions, where not enough information is provided to the player to make the right decision. | |||

Informed decisions where the player is provided with information about the outcome of the decision. | |||

Dramatic decisions are decisions that have their impact on the emotional state of the player instead of in game outcomes. | |||

Weighted decisions are balanced decisions, with consequences on both sides. | |||

Immediate decisions have an immediate impact on the game. | |||

Long-term decisions whose impact whose impact will felt later in the game.<ref>Fullerton, Tracy. Game Design Workshop, A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. Boca Raton, 2019, p. 357.</ref> | |||

Considering those, many decisions in the game turn out to be weighted decisions, because their outcomes turn out to be mostly similar, with only minor differences between them. Furthermore, decisions are mostly immediate decisions with an immediate impact on the player and the game. The most important of the different types of decisions is the dramatic decision, due to the minor long term consequences and the lack of information about the outcome, decisions have most of their impact on the emotional state of the player. Dilemma situations are the most common form in the game. While obvious decisions are not present at all. | |||

====Hocking and the ludonarrative dissonance==== | ====Hocking and the ludonarrative dissonance==== | ||

====Aarseth: categorising between the narrative and the ludic pole==== | In the thesis of Hocking, he describes the problem of the ludonarrative dissonance which occurs when the mechanics of a game are not good implemented within the games narrative.<ref>Seraphine, Frédéric. Is Storytelling About Reaching Harmony?. Tokyo, 2019, p. 3.</ref> A emersion happens because the preferred playing style does not match with the given rules of the game. In ''Spec Ops: The Line'' that occurs because of the choices that are within the game mechanics do not fit in the linear level design where the player has no free choice to explore the levels or try to reach the goal in different ways. Decisions can only be made effecting the story of the game through specific actions, not by playing the game the way the player chooses to do. So the problematics of the ludorrative dissonance are present in the game and can generate a feeling of emersion and not giving the player a certain freedom that seems to be given by the many narrative decisions throughout the game. In other words, even though the player can decide in specific moments to play aggressive or defensive, they has to follow the aggressive story of the game. | ||

====Espen Aarseth: categorising between the narrative and the ludic pole==== | |||

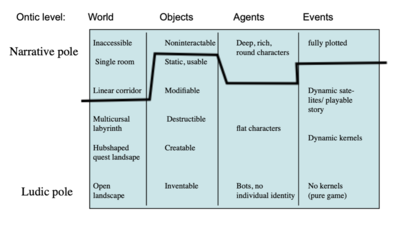

Aarseth developed in his Essay „ A narrative theory of games“ a scheme to categorise games in terms of their narrative or ludic value by considering the World, Objects, Agents and Events in a game. Using that scheme can be used to tell where a game is placed between being very narrative or being very ludic/playful.<ref>Aarseth, Espen. A narrative theory of games. Copenhagen, 2012, p. 3.</ref> | |||

[[File:Bildschirmfoto ludic.png|thumb|400x400px|Ludic & narrative Pole]] | |||

Applying that scheme to ''Spec Ops: The Line'', all of the different categories has to be considered and ranked. When it comes to the world the game features a very linear level building, there are some small optional paths to walk but the start and finish of the level are strictly given. So it is most similar to the linear corridor. The Objects in the game are mostly decorative and help to create the atmosphere. Only ammunition and weapons are usable by the player. Furthermore there are some Objects to collect, but not usable, those are like audio locks and tell a short story about the past. This makes the objects categorised close to the narrative pole between „noninteractable“ and „Static, usable“. Agents are also based close to the narrative pole, by having only a few, but deep and well written characters. Only some characters have minor roles and are less important than the main ones. The emotional connection to those main characters is an important factor that comes in favour of the narrative. | |||

Events are categorised by looking at the kernels and satellites. Kernels are elements, that define the story and are the more important part, while satellites are events that fill the story, and only help to create the discourse.<ref>Aarseth, Espen. A narrative theory of games. Copenhagen, 2012, p. 3.</ref> Events follow static kernels and decisions do not effect the narrative, except for the last decision to make, which leads to different endings. Satellites are more flexible, some decisions have no impact on the narrative or the flow of the game and are just used to fill in the story with a deeper discourse. | |||

====Sicart and ethical approaches==== | ====Sicart and ethical approaches==== | ||

Virtue ethics, based on Aristotelian phronesis, makes it possible to describe ethical relations not only between the objective game and the subjective player but also between the player and the community.<ref>Sicart, Miguel. The Ethics of Computer Games. Massachusetts, 2009, p.111.</ref> In that relationship the player is attached to a passive role, because they has to admit to the ethical rules given by the game and by the community. Ethical wisdom is created by playing a game. Although this approach of video game ethics is not easily applied to ''Spec Ops: The Line'' since ethical behavior is not possible in the given circumstances of a Soldier in war. Decisions that can be made by the player, which are considered as ethical correct are hard to find. The player is forced to make decisions which they (most likely) doesn’t want to do, involving murder of countless soldiers, civilians, children as well as fighting in a war which can’t be won by anyone. Taking war crimes out of the real world and putting them into a video game makes the violation of ethical values less harmful. | |||

Understanding the moral in ''Spec Ops: The Line'' | |||

The goal is to finish the game, is to reach Konrad and stop him from leaving Dubai. On the way to reach that goal, many sacrifices have to be made. The death of countless people, destroying whole buildings and deciding between bad and worse options in dilemma decisions. Reaching the end of the game causes endless pain and suffering for every actor and character in the game. Walker loosing his mind by trying to complete the mission makes him not a hero in the end. He suffers from playing the game as much as his environment. | |||

Should you play the game from an ethical perspective | |||

The decision to play ''Spec Ops: The Line'', especially towards the end of the game makes the player to act against their ethics and does not reward the player with any feeling of satisfaction or reward by completing it. Stop playing might seem as the only option to prevent the events from happening, and to safe the lives of many others and the protagonist. | |||

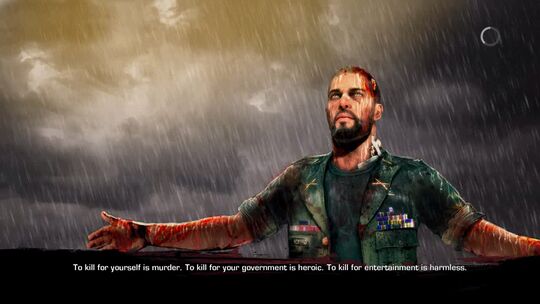

This idea was implemented in the game by different loading screens that break the fourth wall by approaching directly to the player so they start to question the game experience. They make the player realise that committing war crimes might still be inhuman, even if it only happens in a virtual game world. | |||

[[File:Ladebildschirm 1.jpg|left|thumb|540x540px|Loading Screen No. 1]] | |||

[[File:Ladebildschirm 2.jpg|thumb|540x540px|Loading Screen No. 2]] | |||

<br /> | |||

| Line 47: | Line 141: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

==Further Information/ External Links== | <references /><br /> | ||

==Further Information/ External Links== | |||

<references group="Further Information " />3. What we can learn about decision making https://nyphilosophyreview.wordpress.com/2017/06/20/summer-series-what-we-can-learn-about-decision-making-from-spec-ops-the-line/ | |||

4. <nowiki>https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HEPNisyfjnY</nowiki> | |||

<br /> | |||

[[Category:Games]] | [[Category:Games]] | ||

Latest revision as of 20:21, 24 November 2020

Short Abstract on the topics covered in this article.

Please make sure to write the name of the selected game in italic to emphasize its importance.

About the Game

Spec Ops: The Line is the 9th Game of the Spec Ops series that first debut in 1998. Apart from the game title and the genre, a third-person military shooter Game, it has almost nothing in common with earlier releases of the series. All of the other games, released in the Spec Ops series, were released between 1998 and 2002 but none of them were as popular as the most recent release: Spec Ops: The Line. It was developed by the German video game development team „Yager Development“ and was published by 2K Games in June 2012 on Playstation 3, Xbox 360 and Windows. Versions for OS X and Linux were published a few years later. They set their focus more on storytelling and narrative, instead of gameplay, and were inspired by the movie setting for „Apocalypse Now“ which is based on the novel „Heart of Darkness“. Both took a critical view on modern warfare and brutal, inhuman strategies. A multiplayer mode was requested by the publisher 2K Games, which was later developed by the US American Studio „Darkside Game Studios“, since Yager Development wanted to concentrate completely on the single-player campaign.

Spec Ops: The Line tries to separate itself from the classical third person military shooter genre. Most outstanding is the introduction of decision making within the game and using storytelling to show war brutality and the psychological damages caused by being involved in war. In order to create situations in which the player must question his own morality, the game uses dilemma situations with limited time for the player to think them over, which often are a matter of life and death, highlighting the brutality of war.

The Story

Six months before the playable story, Dubai got caught by a series of heavy sandstorms. The situation was kept secret by politicians and the media, while the upper class left the city, leaving behind many people in Dubai. A Battalion, called the „damned 33rd“ from the US Army was on its way back from a Mission in Afghanistan when the sandstorms started and their commander, Colonel Konrad decided to help evacuate the city of Dubai. The Battalion, under his command, took full control over the trapped civilians but could not manage the situation properly. After riots, caused by the lack of resources, like food and water, Konrad started to sacrifice some civilians to save others. This made some members of the 33rd turn against Konrad and his cruel leadership. Many tried to stop him from being in charge and but of them were caught and executed as traitors. A secret squad was sent to Dubai by the CIA and organised the local civilians to stand up against the 33rd. After heavy fights in Dubai between Konrads 33rd and the local people, lead by the CIA, Konrad announced their retreat, and they lead a caravan out of Dubai. But as time passed and the caravan was never seen, the US Army received a brief radio message from Konrad, saying the evacuation failed. The US Army decided to send in a Delta Force Team lead by Captain Martin Walker together with First Lieutenant Alphonso Adams and Staff Sergeant John Lugo. Their mission was to investigate about the situation, to find survivors and a way to evacuate the civilians out of Dubai. The playable story begins with the Delta Force Team arriving in Dubai.

Plot (Spoiler)

After about the first half of the game, things begin to take a turn. Walker starts to slowly loose his sanity, and his visual hallucinations start to appear more and more frequently: Soldiers appearing out of nowhere, landscapes changing when walking past them, flashbacks to past events and dreams of being trapped in an unescapable, hell-like maze. At one point Walker relives the opening scene, realising he’s been going through this before. In the last chapter, when he is finally confronted with Konrad, he discovers that Konrad has been dead for a long time, while he’s talking to him in his imagination, seeing him as a ghost. He also realises he’s been talking to himself throughout the whole game, which explains some of the nonsensical answers he received from Lugo and Adams. Many events turn out to be only products of his imagination and never actually happened in real life.

According to theories and interpretations, popular voices say he already died in the opening scene and everything after that is him being punished for all the crimes and sins he committed in his life, and now he has to suffer in his afterlife to reach purification. What really happened, if any of it happened at all, depends on different points of view and can ultimately only be decided by the player itself.

In the end of the game, the player is given multiple choices. Either they can shoot the imagination of Konrad to mark the end of dealing with moments of insanity. Or the player can choose to commit suicide.

Research-Relevant Topics of the Game

Core Game Mechanics

Controls

In Spec Ops: The Line, the Player takes control of the main character: „Captain Martin Walker“. The basic controls are mostly similar to a classical third person shooter, with the camera looking above the shoulder of the character and other elements such as taking cover behind obstacles, picking up enemy’s weapons and managing resources like ammunition and grenades. You can also make orders to the other members of the Team, Adams and Lugo. You can tell them to concentrate their fire on specific enemies, use flash grenades to blind groups of enemies or push towards a specific direction. In its core, it is played like any other military shooter game. Furthermore, apart from some collectable items that tell a short story about past events, there is not much to explore in the mostly linear levels. The game is split in into total of 15 Chapters, with an average playtime of six to seven hours.[1]

Decision making

The way in which Spec Ops: The Line differs mostly from other games within the third person shooter genre is how the player must decide his own destiny within the story, as oppose to it being pre-determined. All of the multiple decisions that have to be made within a play-through stay inside the basic game mechanics. Decisions are not made by simply selecting one or the other option, by clicking at a certain point or pushing a certain button, but by choosing to perform between two specific actions or not acting at all. In praxis, you are confronted with situations where you have to act in a specific way to make a choice, like shooting a soldier or waiting to let him get away. Or perhaps opening fire or staying quiet so to not loose stealth. These specific decisions can affect the fate of the team as well as the life of the civilians. They also have an impact on the relationship between Walker and his teammates, causing them to react differently. Walker suffers psychologically after a negative outcome and he begins to go insane, which gradually worsens as the game progresses He starts to see visual hallucinations and his behaviour becomes more violent and out of control.

Different types of decisions

Within the game, there are basically only two types of decisions. First there are those that have small or even none direct impact on the story or the outcome of a situation. This type applies for most of the decisions made throughout the game. Their impact is often not clearly shown to the player. Decisions, like this, don’t have any long term consequences or at least not any that are noticeable.

For example:

Relatively early in the game, we see a member of the CIA, called Gould, who wanted to stand up against the leadership of Konrad. He wasn’t successful and got caught instead. He is about to get punished for what his betrayal and is surrounded by soldiers that will execute him in front of a building. To that scene, Walker and his team walks up. They stay hidden, observe the situation and discuss about what to do. Walker, Adams and Lugo discuss if they should open the fire on the soldiers in order to safe Goulds life, while losing their camouflage or if they should let him die but stay hidden. It seams like a real decision where both actions have arguments for and against doing. The team discusses and the player decides by either opening the fire or by waiting until the soldiers executed Gould. There is no indicator that shows the player how much time is given to make a decision.

When decided to save Gould, the soldiers start firing back immediately and call for support. After the battle against a huge wave of enemies, there is a cutscene, in which the Delta Force Team runs to Gould, finding out he died from loosing too much blood due to his earlier injuries.

When decided to stay hidden and not starting fire; The CIA soldiers execute Gould and after that they notice the Delta Force Team in their hideout by accident. They start shooting and a slightly smaller wave of enemies has to be defeated.

Both decisions lead to an almost similar outcome, none of them was the right or the wrong decision. This Example shows how decisions work in Spec Ops: The Line. Only the way the team members talk to each other is influenced by decisions like this one. There are no further consequences neither in short nor in long sight.

Related Research Approaches

Agency & Meaning according to Salen

The whole process of Walker slowly loosing his mind and suffering from psychotic trauma reflects on the player and makes them feel responsible.

Meaningful Play, as described by Salen, develops in terms of the descriptive meaningful play, through the different, possible outcomes of the decision.[2] The player is informed about the short-term possible outcomes, mostly tangible through cutscenes and the conversations between Walker and the other members of the team.

Meaning is, as Salen suggests, is generated by putting the player into bleak situations where they are forced to make a decision in order to prevent the main character from the worst possible outcome, while still trying to survive and complete the mission. Meaningful play is not achieved through long term consequences. It is more about forcing the player to act fast and act within your own moral standards. It is not possible to differentiate the decisions in right or wrong. Most decisions become dilemmas and have negative outcomes only, so the player has to try to pick the one that makes the other characters suffer less.

The process of decision making fits in the semiotic system invented by Salem and Zimmerman, which is their approach to show that the meaning created has to fit within the system it is part of, because one goal of the game is to trigger repentance and to make the player question the whole intention of being entertained by war games and war in general.

Baumgartner

Since Spec Ops: The Line was published in 2012 it fits right in the era where the decision turn happened in video games, according to Robert Baumgartner.[3] But it differences itself from the decisions described by him in the case, that decisions made, are concrete moments of decision making instead of not noticeable decisions made by just playing the game. The lack of letting the player know, whenever he made a decision, that will have consequences later in the game goes against his understanding of agency. Makro-decisions are not present either so it’s not possible to categorise Spec Ops: The Line in one of both categories. It neither fits in a game that uses structural decisions nor in a game that uses substructural decisions to generate agency.

Meaning and agency is suggested but does not apply, except for the last decision in the game. This leaves us with a fake, not existing feeling of agency, while most decisions will not have any impact on the narrative.

Fullerton and the decision scale

Fullerton and the decision scale:

Tracy Fullertons decision scale can be used to define different types of decisions by categorising them based on critical level.

Decisions are split up in five different categories:

- Inconsequential - „No Impact on Outcome“

- Minor - „Small Impact, Direct or Indirect“

- Necessary - „Indirect or Delayed Impact“

- Important - Direct and Immediate Impact“

- Critical - „Life and Death“

Decisions in Spec Ops: The Line may often be categorised as Important or even Critical. The Game tries to suggest a feeling of making important decisions to the player by putting them in situations where they has to decide about other peoples life and death.[4]

But Fullerton takes further differentiations. Some of those sub-categories are present in Spec Ops: The Line and need to be considered.

Hollow decisions are decisions that turn out to have no real consequences at all.

Obvious decisions that are not a real decision.

Uniformed decisions, where not enough information is provided to the player to make the right decision.

Informed decisions where the player is provided with information about the outcome of the decision.

Dramatic decisions are decisions that have their impact on the emotional state of the player instead of in game outcomes.

Weighted decisions are balanced decisions, with consequences on both sides.

Immediate decisions have an immediate impact on the game.

Long-term decisions whose impact whose impact will felt later in the game.[5]

Considering those, many decisions in the game turn out to be weighted decisions, because their outcomes turn out to be mostly similar, with only minor differences between them. Furthermore, decisions are mostly immediate decisions with an immediate impact on the player and the game. The most important of the different types of decisions is the dramatic decision, due to the minor long term consequences and the lack of information about the outcome, decisions have most of their impact on the emotional state of the player. Dilemma situations are the most common form in the game. While obvious decisions are not present at all.

Hocking and the ludonarrative dissonance

In the thesis of Hocking, he describes the problem of the ludonarrative dissonance which occurs when the mechanics of a game are not good implemented within the games narrative.[6] A emersion happens because the preferred playing style does not match with the given rules of the game. In Spec Ops: The Line that occurs because of the choices that are within the game mechanics do not fit in the linear level design where the player has no free choice to explore the levels or try to reach the goal in different ways. Decisions can only be made effecting the story of the game through specific actions, not by playing the game the way the player chooses to do. So the problematics of the ludorrative dissonance are present in the game and can generate a feeling of emersion and not giving the player a certain freedom that seems to be given by the many narrative decisions throughout the game. In other words, even though the player can decide in specific moments to play aggressive or defensive, they has to follow the aggressive story of the game.

Espen Aarseth: categorising between the narrative and the ludic pole

Aarseth developed in his Essay „ A narrative theory of games“ a scheme to categorise games in terms of their narrative or ludic value by considering the World, Objects, Agents and Events in a game. Using that scheme can be used to tell where a game is placed between being very narrative or being very ludic/playful.[7]

Applying that scheme to Spec Ops: The Line, all of the different categories has to be considered and ranked. When it comes to the world the game features a very linear level building, there are some small optional paths to walk but the start and finish of the level are strictly given. So it is most similar to the linear corridor. The Objects in the game are mostly decorative and help to create the atmosphere. Only ammunition and weapons are usable by the player. Furthermore there are some Objects to collect, but not usable, those are like audio locks and tell a short story about the past. This makes the objects categorised close to the narrative pole between „noninteractable“ and „Static, usable“. Agents are also based close to the narrative pole, by having only a few, but deep and well written characters. Only some characters have minor roles and are less important than the main ones. The emotional connection to those main characters is an important factor that comes in favour of the narrative.

Events are categorised by looking at the kernels and satellites. Kernels are elements, that define the story and are the more important part, while satellites are events that fill the story, and only help to create the discourse.[8] Events follow static kernels and decisions do not effect the narrative, except for the last decision to make, which leads to different endings. Satellites are more flexible, some decisions have no impact on the narrative or the flow of the game and are just used to fill in the story with a deeper discourse.

Sicart and ethical approaches

Virtue ethics, based on Aristotelian phronesis, makes it possible to describe ethical relations not only between the objective game and the subjective player but also between the player and the community.[9] In that relationship the player is attached to a passive role, because they has to admit to the ethical rules given by the game and by the community. Ethical wisdom is created by playing a game. Although this approach of video game ethics is not easily applied to Spec Ops: The Line since ethical behavior is not possible in the given circumstances of a Soldier in war. Decisions that can be made by the player, which are considered as ethical correct are hard to find. The player is forced to make decisions which they (most likely) doesn’t want to do, involving murder of countless soldiers, civilians, children as well as fighting in a war which can’t be won by anyone. Taking war crimes out of the real world and putting them into a video game makes the violation of ethical values less harmful.

Understanding the moral in Spec Ops: The Line

The goal is to finish the game, is to reach Konrad and stop him from leaving Dubai. On the way to reach that goal, many sacrifices have to be made. The death of countless people, destroying whole buildings and deciding between bad and worse options in dilemma decisions. Reaching the end of the game causes endless pain and suffering for every actor and character in the game. Walker loosing his mind by trying to complete the mission makes him not a hero in the end. He suffers from playing the game as much as his environment.

Should you play the game from an ethical perspective

The decision to play Spec Ops: The Line, especially towards the end of the game makes the player to act against their ethics and does not reward the player with any feeling of satisfaction or reward by completing it. Stop playing might seem as the only option to prevent the events from happening, and to safe the lives of many others and the protagonist.

This idea was implemented in the game by different loading screens that break the fourth wall by approaching directly to the player so they start to question the game experience. They make the player realise that committing war crimes might still be inhuman, even if it only happens in a virtual game world.

References

- ↑ https://howlongtobeat.com/game?id=8898

- ↑ Salen, Katie. Zimmerman, Eric. Rules of Play: game design fundamentals. Unit 1. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2004, p. 34.

- ↑ Baumgartner, Robert. Prozeduale Entscheidungslogik im Computerspiel, In: Ascher, Franziska. „I’ll remember this“. Funktion, Inszenierung und Wandel von Entscheidungen im Computerspiel, Glückstadt, 2016, p. 258.

- ↑ Fullerton, Tracy. Game Design Workshop, A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. Boca Raton, 2019, p. 356.

- ↑ Fullerton, Tracy. Game Design Workshop, A Playcentric Approach to Creating Innovative Games. Boca Raton, 2019, p. 357.

- ↑ Seraphine, Frédéric. Is Storytelling About Reaching Harmony?. Tokyo, 2019, p. 3.

- ↑ Aarseth, Espen. A narrative theory of games. Copenhagen, 2012, p. 3.

- ↑ Aarseth, Espen. A narrative theory of games. Copenhagen, 2012, p. 3.

- ↑ Sicart, Miguel. The Ethics of Computer Games. Massachusetts, 2009, p.111.

Further Information/ External Links

3. What we can learn about decision making https://nyphilosophyreview.wordpress.com/2017/06/20/summer-series-what-we-can-learn-about-decision-making-from-spec-ops-the-line/

4. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HEPNisyfjnY