Life Is Strange 2: Difference between revisions

From GameLabWiki

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

On the 29<sup>th</sup> of April in 2019 the Life Is Strange marketing team published a video, which explains the decision- and consequence-mechanics of all the Life Is Strange games and compares them to each other. In the end, it talks about the substructural decisions in LiS2. | On the 29<sup>th</sup> of April in 2019 the Life Is Strange marketing team published a video, which explains the decision- and consequence-mechanics of all the Life Is Strange games and compares them to each other. In the end, it talks about the substructural decisions in LiS2. | ||

<youtube>https://youtu.be/Z6NAaMLwWNo</youtube | <youtube>https://youtu.be/Z6NAaMLwWNo</youtube><blockquote>"You could think of the choice and consequence system as not a single snowflake, but a collective of multiple flakes that end up transforming into a tranquille snowscape or a biting blizzard."<ref>https://youtu.be/Z6NAaMLwWNo</ref></blockquote> | ||

==Further Content of the Game== | ==Further Content of the Game== | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| Line 90: | Line 87: | ||

[[File:Wolves ui.gif|none|thumb|Impacting Sean and Daniel<ref>https://life-is-strange.fandom.com/wiki/Wolf</ref>]] | [[File:Wolves ui.gif|none|thumb|Impacting Sean and Daniel<ref>https://life-is-strange.fandom.com/wiki/Wolf</ref>]] | ||

[[File:Wolves ui-Daniel-variant.gif|none|thumb|Impacting Daniel<ref>https://life-is-strange.fandom.com/wiki/Wolf</ref>]] | [[File:Wolves ui-Daniel-variant.gif|none|thumb|Impacting Daniel<ref>https://life-is-strange.fandom.com/wiki/Wolf</ref>]] | ||

In the end of every episode the player finds out what the other players decided for. An internet connection is needed. The decisions are divided in “relevant for Daniel” and “relevant for Sean”. | |||

Especially for the invisible decisions this feature is very interesting because it explains | |||

# that there was a choice option. For example: If the players do not go to Daniel, who is trying to flit stones in episode one, then it will be counted as “Daniel didn´t learn how to flit stones” in the statistics later. The player decides against teaching Daniel without knowing this option. The player, who gives up on Daniel too early while teaching, gets the same result in the end. | |||

# how a decision could affect the story in a different way to what the player could have known. Most of the choices are binary Yes/No options. For example: Sean goes for a swim or not. But in the statistics in the end it is revealed what would have happened, when the player decided differently. The scope reaches from unexpected haircut to death of a beloved character. If the players choose to go to sleep with Daniel and resists Sean´s wish to hang out with the others in episode three, they do not know what they had missed. The statistic explains that Sean could have gotten a haircut. | |||

It is important to mention that the choice statistic does not reveal what the decisions are depending on and how they influence each other. Also, not every little consequence or difference in dialog is listed. So, the player is encouraged to discover these other options, even though most of them are shown in the end of every episode. | |||

A complete list of all decisions in every episode and how they influence the narrative can be found on the fan made Life Is Strange Wiki: | |||

https://life-is-strange.fandom.com/wiki/Choices_and_Consequences_(Season_2) | |||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

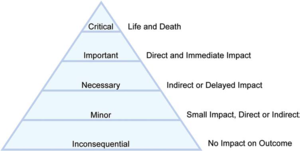

=== Tracy Fullerton´s Decision Scale === | |||

Tracy Fullerton wants to explore, which kind of choice is needed to make videogames interesting. She realizes that that the quality of a decision depends on its influence on the narration. | |||

[[File:Decision scale.png|thumb|529.333x529.333px|Tracy Fullerton´s decision scale<ref>Tracy Fullerton (2019): Game Design Workshop, S. 354.</ref>]] | |||

If it is assumed player-agency is needed to have a satisfying game experience, then a game is only allowed to have few “inconsequential” consequences. One can find all kinds of choices of the decision scale in LiS2, but most of the decisions are the ones on the lowest part of the pyramid. That’s the critique point mentioned in “substructural decisions”. The many choices in LiS2 are at most “minor” but have immediate consequence (for example in dialog options or quick-time-events). On the other hand, the scope of the consequence is little. Some choices have consequences through dialog options, funny commentary or external minor changes of the game figures. But if all decisions count as one big decision, it would be one “critical” decision regarding the final decision of the game. | |||

[[Category:Games]] | [[Category:Games]] | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Revision as of 19:25, 21 September 2020

Life Is Strange 2 is the long-awaited sequel from Life Is Strange, one of the most popular indie-adventures of the last decade. The game series is famous for thematizing queer topics, difficult choice-making, immersive storytelling, and providing the player with a sense of agency. This Wiki will be focusing on these research topics.

About the Game

Life Is Strange 2 (LiS2) is a graphic adventure game developed by Dontnod Entertainment and published by Square Enix. The game is the sequel of Life Is Strange and plays in the same diegetic universe as Life Is Strange: Before the Storm and The Awesome Adventures of Captain Spirit. It is available for Windows, PlayStation 4, Xbox One, Linux and macOS. The story is narrated in five sequential episodes which were published from June 2018 to December 2019. The player follows the Diaz-brothers on their escape from the police to Mexico, after their father was shot by a officer through no fault of his own.

After the death of their father, the brothers Sean and Daniel Diaz run away from home. In fear of the police they are trying to reach Puerto Lobos in Mexico, the hometown of their deceased father. On their escape they encounter many difficulties of social matter, but the greatest challenges come to light when Sean realises his younger brother has a telekinetic power, which he is not able to control yet. Suddenly the sixteen-year-old, half Mexican teenager is responsible for Daniels safety and well-being as well as his education and upbringing. While Daniels power is rising, the player in the role as Sean must decide weather to steal or beg for food or how to spend the night in the wilderness. All that, while also trying to be a good example for his little brother, who is counting on Sean and will be influenced by the players decisions.

Research-relevant topics of the Game

Core Game Mechanics

LiS2 is a graphic, point-and-click adventure game. The player can explore the environment in a third person view by playing the protagonist Sean Diaz. He interacts with objects and talks with non-player characters via dialog. It´s a closed world game where the player must follow the main story quest but has the possibility to look around and examine characters and objects. The player explores the narrative by making decision concerning the plot. Depending on what they decided, the narrative evolves differently. Making decisions is the core game mechanic of LiS2, which gives the player a sense of agency. Therefore, the decisions will be highlighted in the following.

Decisions and agency

As the players must make many decisions throughout the game, they develop a sense of agency. Here one must divide between visible, invisible and substructure decisions. Florian Sprenger´s definition of microdecisions shows that control emerges from decision-making.[1] The person who is deciding controls the situation. If you transfer this thought onto videogames it means that agency and control can be gained with making a choice out of many possibilities.

Janet Murray says about agency that “when the things we do bring tangible results, we experience the second characteristic delight of electronic environments - the sense of agency. Agency is the satisfying power to take meaningful action and see the results of our decisions and choices.”[2]

But especially decision in games are based on a written script which determines the seemingly free choice-making. According to Claus Pias, every gameplay is subjected to a map which builds narrative and guides the player.

„Betrachtet man die Karten von Adventures und rekonstruiert die zugehörigen Spielwege, so wird deutlich, dass es sich nicht um Bäume handelt, sondern um zusammenhängende Graphen mit zwei ausgezeichneten Knoten, nämlich dem ersten Raum s und dem letzten Raum t“[3]

English: „If you look at the maps of adventures and reconstruct the matching game paths, it will be clear that there are no trees, but coherent graphs with two shown knots, namely the first room s and the last room t”

This kind of structure also lies under the narrative of LiS2. The player can decide and also experience the consequences of his actions, but all of that is limited through the substructural system. The narration is steady for most parts because of its narrative linearity.

For example, following situations are not changeable:

- The father’s death

- The plan to escape to Mexico

- Living with the grandparents, Cassidy and Finn or the mother for an episode

- The dog´s death

…and many more.

The way – or story – of the brothers is given. The player has only a few possibilities to change the narrative.

LiS2 has two levels. One is the space for player´s action where he can make visible and invisible decisions, which are responsible for slight changes in the story. The other level lies deeper and is the space for substructural decisions where the game´s system decides for the player on the basis of the players visible and invisible actions, because the ending of the game depends on how the player behaves and communicates with Daniel. On the level of substructure are parameters, which assign behavior of the player to one of the possible endings. More to this point can be found under “substructural decisions”.

Visible Decisions

The visible decisions in LiS2 are shown clearly, when the game flow stops, the game “pauses”, and the player has unlimited time to decide for one of the shown choices. This kind of decision design often appears in situations, where the player must decide quickly in reality. The game takes away the used pressure of fast choice-making deliberately to force the player to really think about their decision. Like that, impulse decisions can be eliminated.

Invisible Decisions

Invisible means, that is it not visible for the player if the decision even has an impact on the story or if it is irrelevant. In contrary to the visible decisions, these are not clearly marked for the player. Only after a decision is taken, a wolf symbol on the right corner visualises/indicates that the action will have consequences. Often the players do not realise that they are doing something that the game remembers. There are also situations where the wolf symbol does not appear although the action will have an impact on the game. Not only dialog options but also quick-time-events and to investigate or not investigate objects, persons and the player´s environment belong to the invisible decisions. Especially the optional investigation can but does not have to have consequences. The name “invisible decisions” is so justified. By this means, the game tells the player that everything they do or do not do could have consequences for the story, but it does not have to. Looking at the number of possible decisions, one can say that the player has agency playing LiS2. What kind of quality the decisions have will be discussed under “Fullerton´s decision scale”.

There is no difference between the visible and invisible decisions concerning the intensity of impact they have on the story. They are equally important.

Substructural Decisions

"Die Basis des Strukturmodells liegt auf der mechanischen 'Substrukturebene' [...] [Sie] kann also als die Summe aller möglichen Einzelaktionen eines Avatars begriffen werden"[4]

English: “The basis of the structure model lies on the mechanic ‘substructure-level’ […] [It] can be described as the sum of all possible individual actions of an avatar”

In Baumgartner´s substructure-model player actions are located in microstructures, which are in turn located in macrostructures. The game registers the player´s actions and makes it dependent on that, how the game ends for them individually. In LiS2 exist seven different endings, which can be presented to the player. The substructural decision is not just a different kind of decision-making design like invisible and visible decision. Rather it is the case, that the substructure lies under the visible and invisible decisions. While these other choice-making possibilities are influencing the story slightly, every decision which applies to the substructure and decides the ending of the plot. By this means, the player can only influence the ending indirectly. The substructure of the game stays hidden for the player. Through visualising consequences with help of the wolf symbol the player can get a sense of the scope of his actions, but it will never be revealed how exactly the consequences – the substructure, the invisible decisions and visible decisions – work together.

In contrast to games like Silent Hill 2 or Metro 2033, LiS2 doesn´t keep track about things like the players movement activity. It focuses more about how the player raises Daniel and how he behaves as a role model.

There are two parameters on the substructure: Daniel´s moral and Daniel´s relationship to his brother.

If the player chooses on the visible and invisible decision level options, which seem to be morally right, they will get an ending, where Daniel is a high moral person who wants to confess to the police. This means that not only one decision, but the sum of all of them are responsible for the individual end of the game.

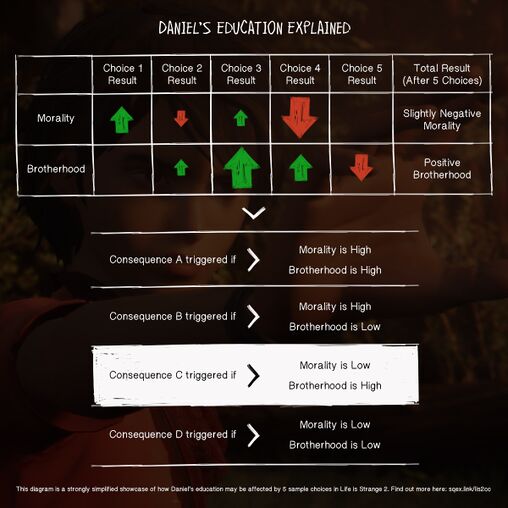

This picture from a LiS2 blog on tumblr visualises this principle:

About the choice-table:

"Choice 1: Sean reminds Daniel that stealing is wrong, in every situation, and refuses to take money from an unattended wallet. Choice 2: Sean ‘borrows’ a can of cola from a store, to quench Daniel’s thirst, and promises he’ll send the store a couple of dollars in the mail when they get some money. Choice 3: Sean stays up late entertaining Daniel with bedtime stories, with wholesome morals, staving off his nightmares and helping him sleep through the night. Choice 4: Sean shoots a potential kidnapper in the arm with the man’s own gun, in order to save Daniel. Choice 5: An angry Sean blames Daniel for having to shoot the man."[5]

On the 29th of April in 2019 the Life Is Strange marketing team published a video, which explains the decision- and consequence-mechanics of all the Life Is Strange games and compares them to each other. In the end, it talks about the substructural decisions in LiS2.

"You could think of the choice and consequence system as not a single snowflake, but a collective of multiple flakes that end up transforming into a tranquille snowscape or a biting blizzard."[6]

Further Content of the Game

Consequences and enlightenment of the player

A wolf symbol on the right bottom corner visualizes if a choice has consequences. The players know if the consequences are relevant for Sean, Daniel or both by the different highlighted wolfs.

In the end of every episode the player finds out what the other players decided for. An internet connection is needed. The decisions are divided in “relevant for Daniel” and “relevant for Sean”.

Especially for the invisible decisions this feature is very interesting because it explains

- that there was a choice option. For example: If the players do not go to Daniel, who is trying to flit stones in episode one, then it will be counted as “Daniel didn´t learn how to flit stones” in the statistics later. The player decides against teaching Daniel without knowing this option. The player, who gives up on Daniel too early while teaching, gets the same result in the end.

- how a decision could affect the story in a different way to what the player could have known. Most of the choices are binary Yes/No options. For example: Sean goes for a swim or not. But in the statistics in the end it is revealed what would have happened, when the player decided differently. The scope reaches from unexpected haircut to death of a beloved character. If the players choose to go to sleep with Daniel and resists Sean´s wish to hang out with the others in episode three, they do not know what they had missed. The statistic explains that Sean could have gotten a haircut.

It is important to mention that the choice statistic does not reveal what the decisions are depending on and how they influence each other. Also, not every little consequence or difference in dialog is listed. So, the player is encouraged to discover these other options, even though most of them are shown in the end of every episode.

A complete list of all decisions in every episode and how they influence the narrative can be found on the fan made Life Is Strange Wiki:

https://life-is-strange.fandom.com/wiki/Choices_and_Consequences_(Season_2)

Tracy Fullerton´s Decision Scale

Tracy Fullerton wants to explore, which kind of choice is needed to make videogames interesting. She realizes that that the quality of a decision depends on its influence on the narration.

If it is assumed player-agency is needed to have a satisfying game experience, then a game is only allowed to have few “inconsequential” consequences. One can find all kinds of choices of the decision scale in LiS2, but most of the decisions are the ones on the lowest part of the pyramid. That’s the critique point mentioned in “substructural decisions”. The many choices in LiS2 are at most “minor” but have immediate consequence (for example in dialog options or quick-time-events). On the other hand, the scope of the consequence is little. Some choices have consequences through dialog options, funny commentary or external minor changes of the game figures. But if all decisions count as one big decision, it would be one “critical” decision regarding the final decision of the game.

- ↑ Florian Sprenger (2015): Politik der Mikroentscheidungen: Edward Snowden, Netzneutralität und die Architekturen des Internets.

- ↑ Janet Murray (1997): Hamlet on the Holodeck, S. 126.

- ↑ Claus Pias (2000): Computer Spiel Welten, S. 174f.

- ↑ Robert Baumgartner (2016): Prozedurale Entscheidungslogik im Computerspiel, In: Franziska Ascher: Funktion, Inszenierung und Wandel von Entscheidung im Computerspiel, S. 262.

- ↑ Life Is Strange Blog: Everything you need to know about Daniel in Life Is Strange 2, URL: https://lifeisstrange-blog.tumblr.com/post/188836949825/everything-you-need-to-know-about-daniel-in-life, aufgerufen am 13.07.20.

- ↑ https://youtu.be/Z6NAaMLwWNo

- ↑ https://life-is-strange.fandom.com/wiki/Wolf

- ↑ https://life-is-strange.fandom.com/wiki/Wolf

- ↑ https://life-is-strange.fandom.com/wiki/Wolf

- ↑ Tracy Fullerton (2019): Game Design Workshop, S. 354.