Metagaming

From GameLabWiki

In the many different video game communities of modern gaming culture, the word metagame is a well-known and often used terminology to describe various forms of gameplay. While in particular game contexts the term is broadly used in a self-explanatory way, a precise definition and differentiation is still unclear. In the academic, this concept has been approached from several perspectives. This page intents to summarize at least some of these intertwining concepts, to give a brief overview about the ongoing development of a clearer academic understanding, about how one can define metagame in context of digital game studies and finally, how to differentiate the many aspects, that are blackboxed in this seemingly universal label.

Introduction

To set a starting point, it is useful to look at a short excerpt from an interview with Stephanie Boluk und Patrick LeMieux, the authors of the book Metagaming - Playing, Competing, Spectating, Cheating, Trading, Making, and Breaking Videogames (2017)[1], which captures the core problem of the topic:

„[…] what do players mean when they say metagame? This word pops up again and again in live commentary and forum discussions around speedrunning, esports, competitive fighting games, massively multiplayer online games, and virtual economies as well as in conversations around collectible card games, tabletop role-playing games, and board games. So we started by wondering if metagame referred to a specific technique, a historical practice, a personal preference, a community culture, or just play in general? Does it mean the same thing across different gaming discourses or is it dependent on context? Is it a productive lens for thinking about videogames or does it pose a challenge to the ways we talk about technical media? And the answer is, as you might imagine, a bit of all the above.“[2]

An Etymological Derivation & The Prefix Meta-

According to Boluk and LeMieux, even it is used this frequently, the word metagame has no appearance in any accessible dictionary. So, to get a first understanding, it makes sense to take a closer look to the etymology of the word itself.

Deriving from the ancient Greek, the word or preposition meta has several meanings. Defined as something behind, beyond, with, after or across etc., in its self-referential characteristic, the prefix meta- „signifies […] the term or concept it precedes“ in a proportion of X about X. For Example a Film about a Film, data about data or in this case, a game about a game. Like Boluk and LeMieux describe, as "a signifier for everything occurring before, after, between, and during games as well as everything located in, on, around, and beyond games, the metagame anchors the game in time and space.“

Main Part

Richard Garfield´s Definiton

Observing the academic discourse that covers research about metagame in the field of game studies, authors like the before mentioned Boluk and LeMieux almost always recur to the definition attempt in the 90es of the game designer and creator of the collectible card game Magic: The Gathering (1993) Richard Garfield.

Coming from a, in his own words, hopelessly idealistic perspective, to look at each played game as a sort of isolated conflict, he realized the huge impact that the surrounding structure has, in which a game is embedded and „how strongly that structure was backed by other people“.

His definition of metagame is: How a game interfaces with Life.

„A particular game, played with the exact same rules will mean different things to different people, and those differences are the metagame.“

He then presents his further differentiation, which ties in with the etymological background of the prefix meta-:

- What you bring to a game. (e.g., equipment like Magic decks and tennis rackets but also personal abilities)

- What you take away from a game. (e.g., prize pool, tournament rankings, or social status)

- What happens between games. (e.g., preparation, strategizing, storytelling)

- What happens during a game, other than the game itself. (e.g., trash talking, time outs, and the environmental conditions of play)

To keep it as short as possible, Boluk’s and LeMieux’s analyses of Garfield’s definition culminates in the understanding, that the metagame - as how a game interfaces with life - is „[…] the only kind of game we play“ and „ […] not just how games interface with life: it is the environment within which games »live« in the first place. Like Mark Hansen’s […] definition of media as »an environment for life,« metagames are an environment for games.“

Alternate Histories of Play - Videogames as Equipment for Metagames

Following a more social-philosophical approach, in which metagaming is the process of human activity to play any kind of game, Boluk and LeMieux raise the question whether video games, as technological artifacts, could be considered not as games in the first place, but rather as equipment for making metagames instead. By stating that "from the position in front of the television, posture on the couch, and proprioception of the controller to the most elaborate player-created constraints, fan practices, and party games, metagames are the games created with videogames", the authors draw the metagame as a material trace emerging out of the "discontinuity between the phenomenal experience of play and the mechanics of digital games“. Its this, what they describe as alternate histories of play „and although everyone alive may be engaged in playing elaborate games, these games remain hidden from view. We don’t simply play games, but constantly (and unconsciously) make metagames.“

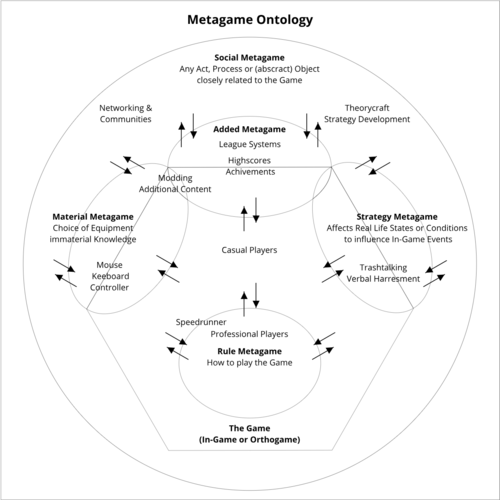

Metagame Ontology

The researcher Michael S. Debus provides a more detailed overview of the various forms of the metagame and connections with other related concepts of digital games in his work "Metagame: The Ontology of Games Outside of Games" (2017). Debus attempts to work out a ontology of metagames to serve as a basis for future research. While keeping in mind that such ontological elaboration, working with abstract heuristic models to frame fluid processes comes with many difficulties, the following presents his five subcategories of metagames: The social metagame, the added metagame, the material metagame, the strategy metagame and the rule metagame. He sets the metagame in generell as an opposing term to the orthogame (as the original program code and its virtual representation), deriving from Carter´s et al. analyses of EVE Online, and also refers to Garfield´s definition attempt, but his main focus is on metagame as a form of higher strategy, like its common used in the electronic sport (E-Sport) scene and communities surrounding competitive games.

Theorycraft and Metagame

In such communities another terminology circulates and has become of academic interest: The term theorycraft originates out of the Starcraft community and was defined within the World of Warcraft (WoW) community as the "attempt to mathematically analyze the game mechanics in order to gain a better understanding of the inner workings of the game". Therefore it has a large impact on the process of how a game is played and in this sense theorycraft relates to the metagame, as the game outside of the game. But Debus, as well as the researchers he refers to, considering the practice of theorycrafting "neither equivalent to, nor completely distinct from metagaming, but as residing within its core, or in other words, as a component of it." In short, he defines theorycraft as the method and theorycrafting as the actual practice of these method to develop a strategy. And in this certain relationship the developed strategy now can be seen as a produced metagame and finally metagaming as the actual execution of the developed strategy. He also states that there are "generally two different types of metagaming. One is the application of strategies to one’s own playstyle, such as different tactics for specific maps. The other is manifested in the development of tools, such as addons and other software, to improve play" (6)

Interesting to mention is that, in regard to Karin Wenz, he describes theorycrafting as scientification of gameplay. Another author, Faltin Karlsen, draws the same line in his work about this topic, when he states: "Theorycrafting is a phenomenon that intersects with several different academic approaches to games. Being an activity where knowledge and learning are core qualities, it also relates to studies of other types of learning communities.“

Social Metagame

As social metagame Debus subsumes "any act, process or (abstract) object that is closely related to the game, but is of a general social nature." He lists networking in generell, therefore gaming communities seemingly in any kind of form. In his list can be found, for example, contacts to join alliances for collaborations, like in WoW, where "it is only possible to fight the strongest bosses in raids that are well organized." Communities for discussing and developing strategys, however, he doesn't list in this category, which can be criticized as later discussed.

Added Metagame

The added metagame includes any additional content to the original game (orthogame), like high scores, achievements or league structures in electronic sports. "While some of these might also be considered frames in social metagames [...], they are different, as the added content sets specific, competitive structures and goals, while the social frames are merely themes within which a game is played ‘as usual’."

Material Metagame

He relates the material metagame to material things, immaterial knowledge or social actions. Drafting an army before a match in Warhammer 40.000, as well as choice of mouse and keyboard can be found in his list. Also the choice of specific software, which connects to addons or modding in a broader sense. He takes to consideration that "such an addition has a potentially larger impact on the act of playing than material equipment in a ‘real life sport’", like the choice of shoes in soccer or rackets in tennis.

Strategy Metagame

The strategy metagame is characterized as a practice outside of the game that attempts to affect real life conditions to influence in-game events, not to be confused with the rule metagame below. For example trash talking or verbal harassment in in-game chats to demoralize the opponent or in a more specific case "the timing of attacks when the victim is potentially offline, due to different time zones or real-life habits (such as working during the day or sleeping at night)", in browser games like Ogame or Tribal Wars, for example, which are always running at day and night.

Rule Metagame

The rule metagames are "prescriptive rules that emerge, through discussion and application of the community, out of the original rules of the game." This category subsumes what is common seen as the metagame of a game in mostly every competitive gaming community: It is how to play the game. Theorycraft and rule metagame are in a close relationship, where the pratice of theorycrafting is the development of strategies, and the rule metagame is the developed and actually implemented strategy in the game: "Through these methods [the theorycraft], the community develops a body of knowledge, which suggest the best way to behave generally, or in specific situations within the game: the rule metagame."

Various Types of Rule Metagames and Rule Metagame Ontology

"To date, the comparison of rule metagames and games has been missing in metagame research. Their possible similarity is not only indicated by the word ‘game’, but also by the fact that players refer to certain practices as ‘playing the metagame’. "

For a more detailed elaboration on this topic based on a game, see League of Legends

Conclusion

- ↑ Boluk, Stephanie; LeMieux, Patrick: Metagaming - Playing, Competing, Spectating, Cheating, Trading, Making, and Breaking Videogames, 2017

- ↑ PennState, Digital Culture and Media Initiative: An interview with Stephanie Boluk and Patrick LeMieux. https://dcmi.la.psu.edu/2018/09/06/an-interview-with-stephanie-boluk-and-patrick-lemieux/, 2018 (Access: 15. April 2020)